Imagine you’ve been cutting grass with a self-propelled rotary petrol mower – like the ones shown in various images in this article.

(You don’t ‘push’ such lawnmowers. They are propelled along by their engines).

You stop the engine to adjust the height of the blade.

While you’re doing that, completely without warning and unexpectedly, the motor restarts of its own accord.

The blade spins into action and you suffer serious injury to your hand as a result.

Statistics from the USA show that there was an average of about 85,000 lawnmower-related injuries annually in the period 2005 to 2015.

The most commonly injured body parts were the hand/finger (22%) followed by the lower extremities (i.e. toes) (16%).

Men were more than 3 times as likely to be injured as women.

The annual number of lawnmower-related injuries showed no decrease during the period 2005 to 2015.

The purpose of this article is to highlight a particular risk associated with petrol-driven lawnmowers.

This risk means that an operator could inadvertently be playing a form of Russian Roulette with a hot mower.

We take our findings from a recent accident case we dealt with. In that case, an employee was injured due to a combination of faulty equipment and a lack of proper training. The facts were as follows.

The mower in question was a large, heavy, powerful, petrol-driven, self-propelled, rotary lawnmower with a 20-inch-wide cut.

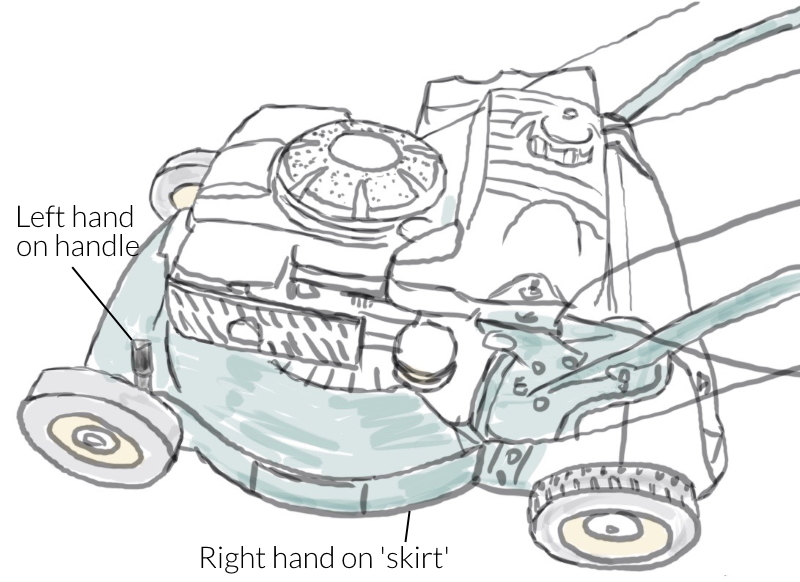

The height of the cutting blade above ground could be adjusted by four individual adjusters, one beside each of the 4 wheels. The mower had a Dead Man’s Handle (“DMH”) which was mounted on the handle used by the operator to keep control of the machine while the mower moved along. A DMH is usually a lever which acts as a safety device by shutting off power when not held in place by the operator. The lawnmower DMH had to be held continually down against a spring for the mower’s motor to stay running.

When working correctly, the DMH when released would stop the motor by disabling the spark to the mower’s single spark plug.

The DMH on the particular mower involved in the accident in question was faulty.

Sometimes it worked properly and sometimes it was ineffective.

The injured person had stopped the mower by releasing the DMH, which appeared to operate correctly, cutting out the motor.

He adjusted 3 of the 4 levers used to alter the cutting height of the blade. While adjusting the final lever, the motor started unexpectedly and the rotating blade injured his right hand.

It is important to note that, on the day, the mower had been in use for some time prior to the accident, so the motor was hot.

The difficulty for the injured person was that the opponent did not regard his account of how the accident happened as credible.

The opponent – his employer – insisted that the mower’s intrinsic safety system would always protect the operator against an unexpected start-up of the motor.

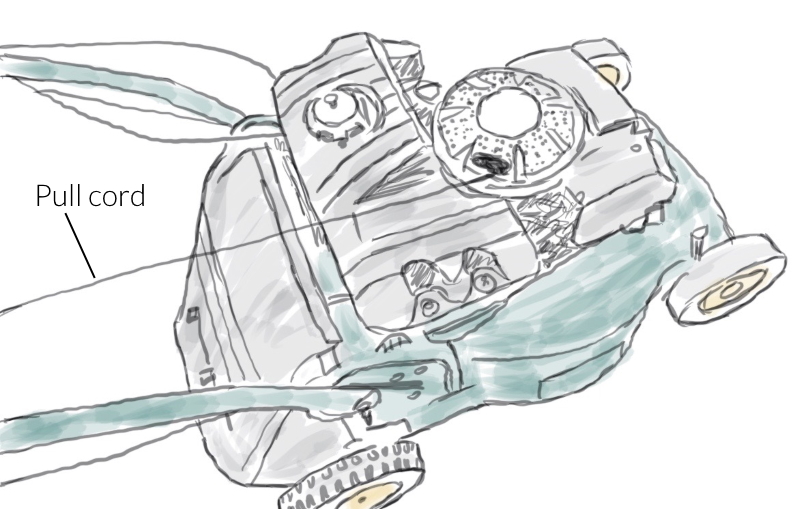

The ‘normal’ method of starting the mower was by a sharp tug on the mower’s pull-cord. This turned the engine, activating the magneto, which produced the spark required to fire the engine into life.

Anyone who has ever operated a self-propelled petrol-driven lawnmower will be familiar with the pull-cord mechanism. Magnetos are common across a range of applications, including chainsaws and propeller-powered aircraft.

The safety manual for the mower cautioned that the machine’s spark plug should be disconnected before any maintenance was carried out on the mower.

There are numerous references on the Internet to the dangers of working on a petrol-driven mower without disconnecting its spark plug.

“If you have a petrol mower, first remove the spark plug from the engine before doing any maintenance work. If you fail to do so, the mower engine could start if you simply rotate the blade with your hands when you clean it.”

“Disconnect spark plug to service. Disconnect the spark plug when you work on the mower. This prevents the engine from accidentally being started. Many people are hurt every year because mowers start unexpectedly when the blades are turned by hand.”

The above references come from Safety Tips for Working with Lawnmowers by Capricorntech.com, dated 26 July 2017.

“At no time should the operator reach under the housing, deck or guards to try making any adjustments or clearing the mower of grass unless the motor has been shut off and the power or spark plug wire has been disconnected. A hot gasoline engine could start of its own accord if the blades are turned while the plug wire is attached.”

(U.S. National Safety Council, Data Sheet 464, Rev. May 2005, para. 25).

The injured person had received some safety training on working with the lawnmower.

However, it was not clear from his training in what circumstances his employers expected the spark plug to be disconnected.

There was a culture of adjustments to lawnmowers being carried out without disconnecting the spark plug, which was condoned by management.

The argument here was that the injured person, although they had received some training, had not had properly explained to them what the difference was between “adjusting” the mower and “maintaining” the mower – and when spark plug disconnection was regarded as essential.

Analysis of the particular lawnmower and the likely effects of the defects in the machine at the time led to the following analysis of the most likely way in which the accident occurred.

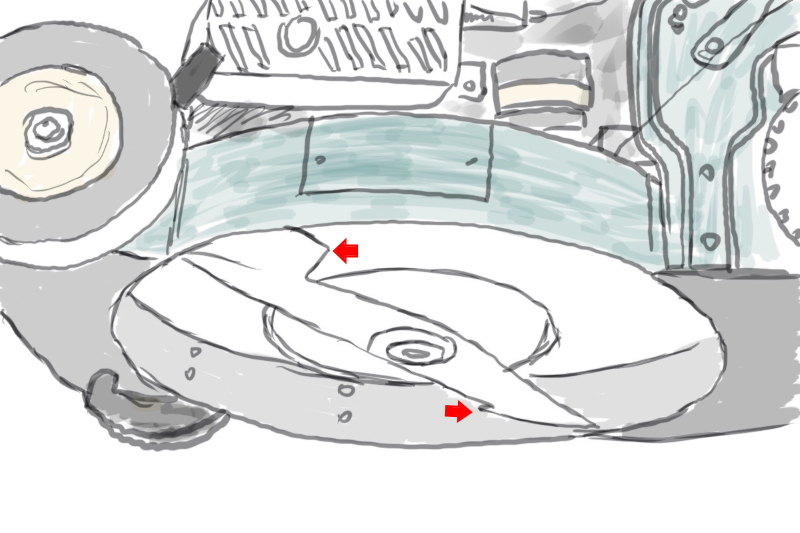

Number one: The position of the cutting blade at the time the operator was adjusting the blade height.

This was obscured from the operator’s view because it was on the underside of the mainframe of the lawnmower. Unknown to the operator, on the particular occasion, the blade had stopped just in front of where the operator’s right hand was positioned while moving the lever to adjust to the height of the blade with his left hand.

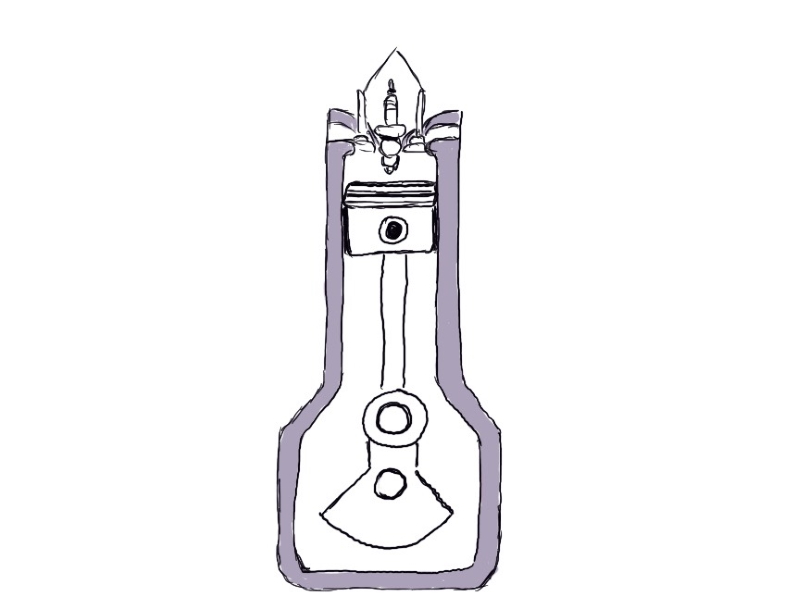

Number 2: The 4-stroke engine had stopped in its compression cycle at about 40 to 60° before top dead centre.

This position can be seen by reference to the illustrations below, which show the 4 stages in the cycle of a Four-Stroke Engine and what ‘top dead centre’ looks like.

It had also stopped with an explosive petrol and air mixture in the cylinder and this explosive mixture was still present when the operator was adjusting the height at the fourth wheel.

Number 3: Working in wet weather conditions, the operator’s right hand slipped while adjusting the lever with his left hand.

Thus, inadvertently, the operator pushed the blade round in what was its normal direction of travel when powered by the motor. This hand-activated motion of the blade caused the motor to rotate (the blade being attached to it) through its compression cycle.

Number 4: The motion of the blade was fast enough to generate a spark.

The motion was fast enough to cause a spark to be generated by the magneto. The spark ignited the explosive mixture in the cylinder causing rapid rotation of the motor in its running direction. The cutting-edge of the following blade to the one the operator’s right hand had pushed to the left, caught his finger and caused him his injury.

Number 5: The DMH (Dead Man’s Handle) was faulty.

If operating correctly, the blade would have been very hard to push because of the brake the DMH applied and also because the spark would be suppressed. The faulty DMH meant that there was no failsafe mechanism to prevent the accident to the injured person.

It might be said that the chances of all 5 of the above factors/events happening at once was very unlikely. That is true. The problem is that there is no easy way to know whether any or all of these factors are ‘aligned’ any time you stop a mower to examine or work on it.

Summary

Power tools are hazardous. Lawnmowers can, for example, cause injury by stones or other materials thrown up by the high-speed blades.

This article has looked at the risk of injury to operators’ hands and feet when they come into contact with the revolving blades.

The standard safety advice in the manuals which come with petrol-driven lawnmowers stresses the need to disconnect the spark plug if the lawnmower is to be adjusted in any way. Such a requirement to partially ‘dismantle’ the machine means it is impossible that it can come to life again until the spark plug is reconnected.

It is easy to become lax in following this instruction, however. When it normally takes such effort to restart a petrol mower with its power cord, the risk of the mower accidentally restarting from ‘off’ of its own accord seems remote, even impossible.

Unfortunately, a ‘hot’ (i.e. recently operated) petrol engine always poses a potential risk of restarting unexpectedly. While that may only be a very slight risk, the scope for a life-changing injury if the motor does suddenly erupt into life is significant.

In essence, you are playing a form of Russian Roulette where your chances of losing are significantly less than 1 in 6 (1 chamber with bullet plus 5 more empty chambers). If you had to choose between ‘revolver roulette’ and ‘lawnmower roulette’, the lawnmower option gives you much better odds of avoiding injury or worse. But when eliminating the risk completely is simple and easy, why should you have to take any chances at all?

The basic safety advice you should follow for petrol-driven lawnmowers includes:

- Always disconnect the spark plug if you will be working on or adjusting the lawnmower. It’s usually easy to do as the spark plug and its connector lead are prominent on the outside of the lawnmower. You just pull them apart to disconnect.

- Keep your hands and feet away from the blade(s).

- If you think a particular adjustment (e.g. to the blade height) might need your hand(s) to be close to the blade, consider whether the adjustment can be made from a standing position at the front or back of the lawnmower (rather than kneeling at its side, which will probably be riskier).

How we can help

In this article, we have tried to highlight a small risk with ‘hot’, petrol-driven lawnmowers which, if the risk materialises, will probably have ‘big’ (and bad) consequences.

It’s a risk from a type of equipment which is often used at work. If you have any questions about this article or about our wider compensation claims services for work-related injuries please get in touch with us.

All initial enquiries are at no cost and without obligation to take matters further with us. You can contact Peter Brash or Marie Morrison in our Elgin office on 01343 544077. Alternatively, you can send us a Free Online Enquiry.