Who you claim compensation from via a personal injury claim is not always as obvious as it may appear.

In a road traffic accident, it’s the negligent driver who injured you that’s first in line. But it’s usually their motor insurer who pays the compensation. And it’s that insurer you will sue if you have to raise a court action to ensure your claim succeeds and you secure a reasonable level of compensation.

If the driver was at work at the time of the accident, you might also have a claim against the driver’s employers under the law of vicarious liability.

What do we mean by vicarious liability?

“Vicarious” experience is where you live your life through the experience of another person, as a housebound parent might experience the wider world through their student child reporting back on travels during a gap year.

Or a precocious child, such as Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes, might claim that his Dad is trying to live Calvin’s life vicariously because Calvin’s Dad’s life is otherwise so dull (Calvin’s Dad is a lawyer, after all).

— Calvin and Hobbes (@Calvinn_Hobbes) 29 December 2018

Through vicarious liability, employers can be held responsible for the negligence or breach of duty of their employees in the course of their employment. The employer gets the dubious honour of the blame for something they did not do personally or perhaps even know about at the time.

An important question in practice is whether the person who caused an injury has any assets with which to pay the compensation.

This is particularly the case in personal injury and death cases, where the compensation may be large and the negligent person responsible may have little money or be uninsured. In these situations, it is in the injured person’s interests to find more than one person responsible and preferably at least one person (or organisation) which is insured.

When I was learning about the law of vicarious liability at Uni in the 1980s, it was a much simpler concept than it has become 30 years later.

Employers have always been able to argue against incurring vicarious responsibility if they could show that the employee was somehow outwith the scope of their employment at the time of the accident.

There is a wealth of decided cases from the courts, ruling on whether an employee’s injury-causing actions were outwith the scope of their employment at the time.

So, in one case from 1974, a bus conductor assaulting a passenger with his ticket punch was not covered by vicarious liability because that was not “managing the bus”.

In jobs which involved travelling while at work, deviating from a normal or direct route might be argued to take the work at that time out of the scope of employment.

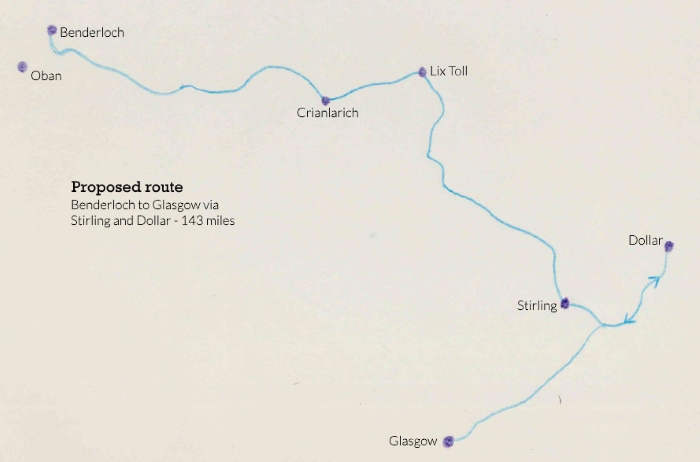

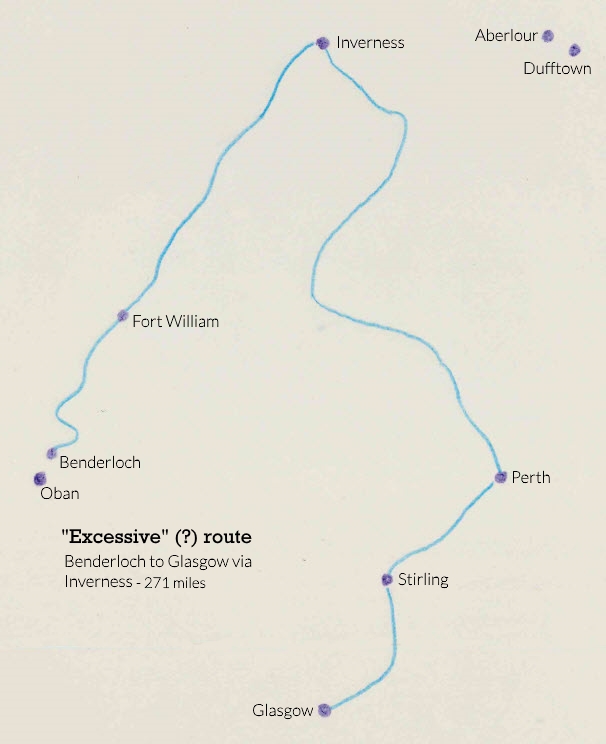

In a Scottish case from the 1960s (Williams –v- Hemphill), a group of boys from the Boys’ Brigade, travelling in a lorry back from a camp at Benderloch (near Oban) to Glasgow, persuaded their driver to detour via Stirling and Dollar so they could “help” a group of Girl Guides they had met during their time in Argyll.

After Stirling but before Dollar, due to excessive speed, the driver lost control on a bend and the lorry left the road and crashed.

Had he safely completed the journey by the route he was taking, he would have travelled about 148 miles as opposed to 97 miles by the normal route.

Williams – who had not been involved in the discussions about the detour – was injured and claimed compensation from the driver’s employers for the driver’s negligence.

The employer argued the driver was on “a frolic of his own” at the time of the accident and, because of that, the employer should not be vicariously liable for the driver’s negligence.

The House of Lords, at that time the highest court in the land, accepted that there might be limits to how far deviation from a route could still leave an employer with responsibility.

Had the driver gone from Argyll to Glasgow via Inverness, for example, that might have been taking things “too far”.

However, in this case, just because the driver chose a route which was contrary to his instructions, it did not take him outside the scope of his employment and his employers were vicariously liable.

In the 21st century, the law on vicarious liability has seen increasing expansion.

In a 2001 decision, the House of Lords decided that the actions of the warden of a residential home in sexually abusing children in his care were so closely connected with his employment as to warrant the imposition of vicarious liability on his employer.

An obvious development was increased willingness on the part of the courts to find “employers” responsible for deliberate acts by employees, such as assault (as opposed to only negligent acts, such as careless driving).

Using the analogy of the lorry carrying the boys from Benderloch to Glasgow, in each case, the court has to determine whether things have gone too far to make it fair to find the employer vicariously responsible.

Assault at the Christmas Party

It’s well known that office Christmas parties are generally viewed as an extension of the workplace and misbehaviour there could lead to disciplinary action being taken against an employee.

Could a company be vicariously liable for injuries caused by an employee after a work Christmas party had ended?

The case of Bellman –v- Northampton Recruitment involved an assault of a (less senior) manager (Mr Bellman) by a (more senior) director (Mr Major) after a Christmas party. Following the official party, the two men, along with other colleagues, went on to a hotel and continued drinking until the assault occurred at about 3.00 am.

Mr Bellman suffered a serious brain injury and the decision was taken to sue the company (or, more exactly, its employers’ liability insurers), rather than the director personally.

Mr Bellman’s claim was unsuccessful at first. The judge who heard the evidence took the view that the company could have been liable if the blow had been struck during the Christmas party itself. But, in the judge’s view, the assault in the hotel occurred after the party during a private drinking session and so the company was not vicariously liable.

Mr Bellman appealed to the Court of Appeal and they found in his favour. They said that, despite the time and place of the assault, Mr Major was purporting to act as managing director of the company at the time. He was exercising the very wide remit which had been granted to him by his employers. He was the “directing mind and will of this small company”. The attack on Mr Bellman had arisen out of a misuse of the position entrusted to Mr Major as managing director.

Summary

Altercations at the office Christmas party – or any office party – are more likely to give rise to liability, following Clive Bellman’s case. It’s an important reminder to businesses that they could be held responsible for improper behaviour at works events, especially where alcohol is allowed to flow freely.

From an employee point of view, in theory, while you could be disciplined for misconduct outwith the workplace in any event, this case arguably extends the legal definition of the workplace even further than previously understood.

It’s a difficult area of law – one where judges frequently disagree.

The trial judge in the Bellman case, referring to vicarious liability, said: “The rule must have proper boundaries; it is not endless.” But, of course, as far as the higher court – the Court of Appeal – was concerned, he got it wrong. He drew the boundary in the wrong place.

In geographical terms, we might say that he thought he was looking at a journey from Benderloch to Glasgow via Inverness whereas, in fact, it was only via Dollar.

How we can help

We hope you found the information in this article to be helpful.

It is important to understand why employers face greater risk from injury claims due to employee negligence (and deliberate conduct) than has perhaps ever been the case.

If you have any questions arising from this article, please get in touch with us. The same applies if you would like to ask about any aspects of our personal injury claims services, generally.

All initial contact is at no charge and without obligation to take matters further. Call us on 01343 544077 or send us a Free Online Enquiry.

Make A Free Online Enquiry Now

P.S. If you need advice in connection with an employment law matter arising from an issue of this type (e.g. a disciplinary procedure or a summary dismissal), contact Moray Employment Law for advice.

Image credit: Article header image (dollar bills): Photo by Madison Kaminski on Unsplash