Have you ever panicked that you have mislaid your mobile phone?

And that while you are in the middle of a conversation with someone on your mobile phone?

This happens to me regularly.

So many things compete for our attention and so much of the activity that fills our day is done almost unconsciously, on autopilot.

The repetitiveness of everyday life dulls our concentration and our short-term memories. Sometimes distractions can be a source of danger, whether that’s while you’re descending the stairs in your house or crossing the street or working on a production line.

In this article we are going to concentrate on accidents at work.

We will look at 3 different accident scenarios where you might think the injured employee ‘should have known better’ yet still claimed successfully. Firstly, we’ll look at the case of the exposed window cleaner. Then, we’ll go on to consider the case of the labourer with inappropriate footwear. Finally, we’ll go over the case of the bus mechanic with the short memory.

So first of all to the window cleaner.

Mr Christmas worked for General Cleaning Contractors as a window cleaner in London. He had 20 years’ experience.

On the day he was injured in December 1948, he was cleaning a sash window, which had separate top and bottom sections. He was at first floor level, 27 feet up. (27 feet – about 8 metres – is approximately the length of a London bus).

At that time it was standard practice for window cleaners to clean the outside of windows by standing on the windowsill. They positioned the 2 parts of the window so they had a handhold. Unfortunately, on this occasion one of the sections moved unexpectedly.

He lost his balance and fell to the ground, suffering serious injury.

His claim was valued at £3,500 – about £100,000 in today’s money.

The employers argued that his claim should fail. He was experienced in his job. The possible safety precautions suggested by Mr Christmas – e.g. working from a ladder – were not practicable, they said. Anyhow, it was the usual thing for the men to clean windows by standing on the sill.

The court found in favour of Mr Christmas.

The judges considered window cleaning to be a dangerous occupation.

The employers should have taken proper steps to protect Mr Christmas from the dangers. They should have laid out the work more carefully. They could have required the cleaning to be done from a ladder instead of from the sill. Another way would have been to ask the building owner to allow the employer to insert hooks into the brickwork so as to allow a safety belt to be attached.

In the House of Lords (the forerunner of today’s Supreme Court), Lord Oaksey famously said:

‘Workmen are not in the position of employers. Their duties are not performed in the calm atmosphere of a boardroom with the advice of experts. They have to make their decisions on narrow windowsills and other places of danger, and in circumstances in which the dangers are obscured by repetition.’

The case demonstrates that where hazards are involved, which thought or planning might avoid or reduce, the employer should do something about them. It may not be sufficient for the employer to leave the thought or planning to the skill and experience – however great – of the man who carries out the work.

Now let’s move on to look at another case where following a common industry practice was not a defence the employer could rely upon.

This is the case of the labourer.

Michael Cavanagh was seriously injured in an accident about 3.30pm on 27 October 1953. He had been working on the roof of a factory at Linfield Road, Belfast, which was owned by his employers, Ulster Weaving Co. Ltd..

At the time, he was helping a colleague, Reilly, who was pointing ridge tiles. The roof had a series of ridges. On one side of each ridge the roof was slated. On the other side, it was glazed. It meant there was a series of ridges and gutters where the tops and bottoms of the alternate slated and glazed sections joined up.

Cavanagh had to carry buckets of cement up to the roof for his colleague.

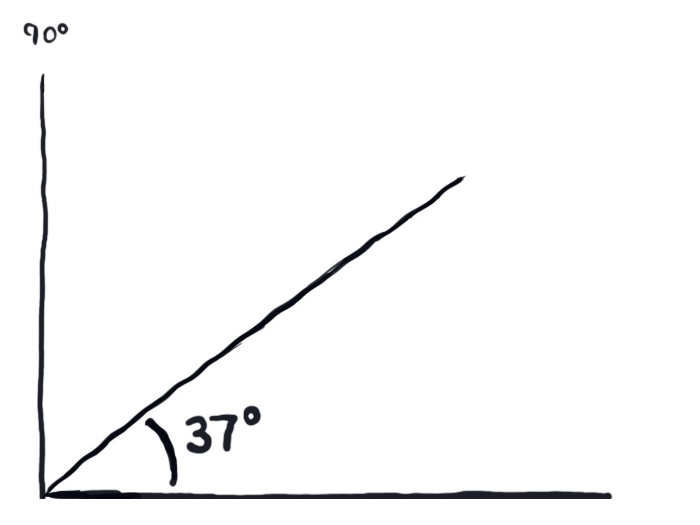

To get to where Reilly was working, Cavanagh had to climb a ladder from the yard. He then traversed a plank gangway balanced across the ridges in between. When he reached the area where Reilly was working, he had to get to gutter level by descending a ladder laid flat against the slated section. The ladder was about 11 feet long. The angle of the slated roof was 37 degrees from the horizontal.

This was a steep slope. See the illustration below. See also this brief YouTube video where the chap has difficulty even with a 30 degree slope – i.e. less steep than Cavanagh’s roof.

Cavanagh’s bucket of cement, which he carried in one hand, weighed around 3 stone (about 19kg).

By the day of the accident, Cavanagh had been doing this routine for over 3 weeks.

Had he not needed to carry a bucket, he could have crawled down the ladder. As it was, he walked down the ladder as if it was a flight of steps, facing down the hill. He had done this many times without incident.

That morning, Cavanagh had been wearing shoes. However the gullies became wet and, for the afternoon session, his foreman gave him a pair of wellies to wear. On reaching the roof ladder beside Reilly, Cavanagh laid his bucket of cement down on the plank gangway. He stepped onto the second or third rung of the ladder. Then he turned and picked up the bucket. He was about to descend to the gully.

As he described it, “my feet just left me”.

He slipped down the slope and slammed into the glass at the bottom with his right side. Though he did not fall through the glass, he broke it. He suffered severe lacerations and his right arm had to be amputated above the elbow.

Cavanagh’s damages claim against his employers was initially decided by a jury. They found in his favour, valuing the claim at £6,520, but reducing the award by 10% to £5,868 (about £135,000 today, adjusted for inflation) in view of a finding of contributory negligence.

The employers appealed successfully to the Northern Irish Court of Appeal.

Again, “common practice” was important. A civil engineer called as an expert witness for the employers said: “For the type of access to building work I would say that it is perfectly in accord with good practice. I have very considerable experience of such work on roofs for over 20 years.”

Cavanagh appealed that decision to the House of Lords.

They granted the appeal. The jury’s decision was reinstated.

The important points for the House of Lords were that Cavanagh was faced with carrying a heavy bucket of cement, down a roof (or crawling) ladder, in an upright position on a slope of 37 degrees without any adequate handhold and wearing rubber boots which were wet and would naturally tend to slip from the somewhat precarious grip which his heels had on the rungs of the ladder and which, further, were probably two sizes too large for him.

The fact that the employer set up a system of work that was standard practice in the trade at that time did not give them a cast-iron defence.

The practice was clearly hazardous and so negligence was proved.

We’ve considered two cases from the 1950s and for our third case we’ll come rather more up to date.

The case of the bus mechanic.

George McEwan was employed by Lothian Buses as a probationary street fitter maintaining and repairing buses at their Edinburgh depot. On 14 April 2002 he had an accident at work, suffering a minor injury to his right hand. He was working alone and unsupervised at the time.

It was accepted that McEwan had slipped on a board that was partly covering an inspection pit at the depot. A spillage of coolant fluid (a mixture of water and anti-freeze) had made the board slippery. He had injured himself trying to break his fall.

There was a dispute about who had spilled the coolant.

McEwan maintained that it was someone else’s fault. However, after detailed consideration of the evidence, the Court of Session judge held that it was McEwan himself who spilled the coolant on which he slipped.

Believe it or not, the claim still succeeded. The employer was in breach of its statutory duty to make sure the floor did not become slippery, so far as reasonably practicable. Lothian Buses were not justified in simply accepting or condoning spillages as a fact of life.

It ought to have been possible for Lothian to devise methods preventing coolant from contaminating the floor.

They provided no evidence to show that it was impracticable. The judge himself mentioned the possibility of spreading absorbent granules on the floor ahead of any job that was known to include the likelihood of spilled coolant.

Despite that success, however, the judge (Lord Emslie) considered that McEwan himself must bear the major share of responsibility for what happened and he assessed contributory negligence at 75 per cent. In other words, McEwan received only 25 per cent of the value of his claim – which amounted to £1,125.

But wasn’t McEwan lucky to get anything at all? Not only did he slip on something he must have known was there, his version of who spilled the coolant was not accepted and so at best he was being economical with the truth. Lothian Buses argued it was 100% his fault.

Maybe he was lucky. Others have done arguably less stupid things at work and been found entirely to blame. We could have gone on to discuss the case of Mr Sharp and his ladder (he footed the ladder using a cushion) but that’s in another article which you can read on this website.

Summary

The courts accept that workers concentration levels are not constant. They will have lapses in concentration. They will not be paying full attention at all times. We may have lapses where we fear we have mislaid our mobile phone – while we are in the midst of talking to someone on that device.

In a workplace context, the main place to look for a duty is with the employer.

It is the employer who must, for example:

- implement a safe system of work;

- provide safe plant and machinery and make sure that work equipment is maintained in an efficient state;

- avoid the necessity for manual moving and handling and, only if that cannot be avoided, properly risk assess the manual handling options so that the risks associated with manual handling can be reduced to the lowest level reasonably practicable.

We can see from the three cases we’ve discussed that the courts are understanding of the reality of daily work.

Workers’ minds are not always on the job. Employers have to take this into account when assessing risks and devising systems of work.

If you or a colleague slips up at work and you are injured, the courts will not jump to the conclusion that it was entirely or partly your fault. Instead, the initial focus will be on what your employer (or the person in control of the workplace) ought to have implemented by way of safety measures.

A lesson to take from this is that you should never prejudge your chances of success with a personal injury compensation claim.

Don’t give up too quickly.

Get some specialist legal advice as soon as possible. You may discover that where you thought your chances of claiming successfully were poor or nil they are, in fact, good.

How we can help

We hope this was a useful article – looking at ways of claiming successfully for an accident at work though you did something silly. In the cases we considered, “silly” included:

- standing on a first floor window ledge to clean the windows;

- wearing rubber boots that are too big for you while descending a steep and slippery slope; or

- spilling fluid on the floor, forgetting it’s there and falling over on it.

If you have any questions arising from this article, please do get in touch with us.

Should you need advice on a possible personal injury claim and you think a free case assessment would be helpful to you – and we are local solicitors from your point of view – go ahead and send us a Free Online Enquiry.

The sooner that someone gets started on the process of investigating and reviewing your claim, the better for you.

The article HERE will help, if you want to understand more about what will actually happen if you get in touch with us about making a personal injury compensation claim.

Our aim is to help people in Moray to claim fair and full compensation for personal injury in such a way that it costs you nothing, whether your claim succeeds or not. We are specialist, accredited solicitors – at Grigor & Young LLP, Elgin.

You can call us on 01343 544077 or you can send us a Free Online Enquiry.

Make A Free Online Enquiry Now

A link you might like

If you live in Moray, you may find our eBook Claiming Compensation for an Accident at Work in Moray is a useful read. Find out more about it and, if you wish, download it free via this page in the Accidents at Work section of the Grigor & Young website (Moray Claims is a trading name of G&Y).