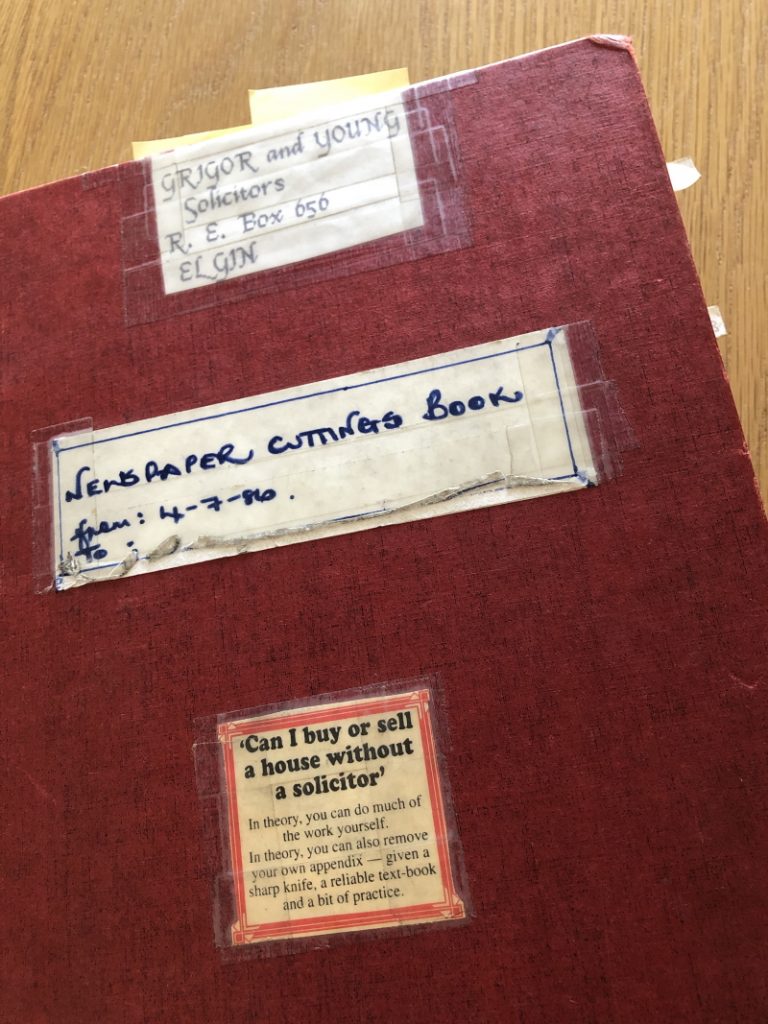

“Can I buy or sell a house without a solicitor?”

Grigor & Young have newspaper cuttings books back to the 19th century, and that’s how one cutting from the mid-1980s is headlined.

The body text continues:

“In theory, you can do much of the work yourself.

In theory, you can also remove your own appendix – given a sharp knife, a reliable textbook and a bit of practice.”

Seth Godin picked up on this theme of expertise in a post on his daily blog.

He asked: “Okay, how hard can it be? (to be an expert). Actually, it might be very hard. Actually, expertise has value. Actually, just because someone said it on the internet doesn’t mean it’s true. Or useful.”

What’s the chance you’d be able to do such conveyancing or (especially) surgery yourself?

Limited, you would think. Less than 10%? Less than 1%?

And a small chance is what you would expect to have, in general, if you were hoping to overturn a finding of 10% contributory negligence in a personal injury claim.

In a contributory negligence situation, your claim succeeds but a percentage gets knocked off (10% tends to the minimum) to reflect the fact that you had a share in the blame. That your losses were partly your own fault too.

What do you think your chances would be of appealing one court’s decision to a higher court to convert a 90% successful claim into a 100% successful claim?

In those terms, 90% seems pretty close to complete success. It’s not exactly the same as gambling, but if you had £9,000 “in the bank” would you stake the whole amount to increase your total winnings to £10,000 (i.e. £1,000 more than you’ve got).

In this article, we’re going to consider a case where that’s what the claimant managed to do successfully.

He appealed a finding of 10% blame on him in order to reduce it to nil and get 100% of the value of his claim.

We’ll consider 3 separate elements here. Firstly, what were the facts of the case? Secondly, why are appeals on contributory negligence often difficult and risky? And, finally, how did the claimant fare in his appeal and what can we learn from it?

How did the claimant get injured?

Mr Casson injured his arm and hand in a workplace accident, after his glove got caught in a moving conveyor belt.

At the time, he was cleaning the surface of a piece of machinery positioned immediately below the conveyor.

The conveyor belt ran continuously throughout the day. It was not possible for Mr Casson or his colleagues to clean the machine when the rollers were stopped.

He was an experienced employee but he had never been given any training or instruction in how the cleaning task was to be carried out. He had learnt what to do by watching what his colleagues did. You had to climb a ladder first of all and that ladder was generally left in place so workers could get up high enough to knock or brush debris off the side of the machine.

The claimant was doing the job in exactly the same way as had been adopted by his fellow employees.

As the judge had said, the claimant had observed others doing this and so, in climbing the ladder to knock or brush debris off the side of the machine, he was not acting on a whim or doing something he had never done before.

Also, the ladder which he was using was already in place and had been there for some time for the very purpose of doing what he was doing on the particular day.

Though he was doing the job in the way everyone else did it, the judge who heard the case knocked off 10% from his compensation for contributory negligence.

This was on the basis that, in giving evidence, Mr Casson had accepted that his actions were risky in putting his hand close to the moving parts.

So, Mr Casson got 90% of the value of his claim but he was advised to appeal the decision.

The argumant was that hee should not have lost any of his compensation.

This seems quite brave and, moving on to part two of this article, it’s worth considering how appeals work.

There are several problems with appeals which are maybe not immediately obvious.

A big difficulty with appeals against courts’ decisions is that the appeal court does not just rehear the case from scratch.

With contributory negligence, unless the judge has made a big mistake in understanding the law or split the blame between the parties way wide of the mark, you’re not going to get anywhere.

And if you get it wrong, you’ll have your own and the other side’s court costs to pay due to losing the appeal.

Having said that, in other articles, we’ve looked at cases where an appeal led to a child getting 50% compensation where originally she got nothing and where, over a series of appeals, the percentage received by the injured child – from an accident in Aberdeenshire – increased from 10% to 30% and finally 50%.

Appeals on contributory negligence can and do succeed.

Let’s see what happened to the appeal in Mr Casson’s case.

He was successful.

The English Court of Appeal overturned the finding that Mr Casson was 10% to blame and awarded him full – 100% – compensation.

What Mr Casson had done in getting injured might be classed as an error of judgment as to the best way to carry out the work. You might also describe it as momentary inadvertence.

Neither of these things could be classed as contributory negligence, however.

Conduct by someone at work which amounts to a mere error of judgment as to how the work in which the person is engaged should best be carried out – or possibly only a mere momentary inadvertence – is not negligent conduct.

In the view of the Court of Appeal, it was powerful evidence in Mr Casson’s favour that every other employee who cleaned the machine did exactly what he had done. Seen in that light, his conduct fell a long way short of contributory negligence.

Let’s have a summary of what we’ve covered here.

Summary

Fortunately, Mr Casson did not have to take a risk to the extent of relying on his own expertise to appeal the judge’s decision (as in doing his own conveyancing or operating on his appendix).

He received accurate advice from his solicitors. Yet it still took some amount of courage on his part to appeal when the losing margin before the first judge had been a fairly small amount of compensation in percentage terms.

But his case shows us that engaging in ‘risky’ activity is not in itself enough to justify a finding of contributory negligence. And where you do your work in line with an established practice, as Mr Casson did, that’s a strong argument against contributory negligence.

How we can help

We hope you’ve found this a helpful explanation of why you shouldn’t jump to feeling to blame if you’ve been injured in a situation where you took a risk.

If you didn’t have a choice in the matter and if you were following ‘standard procedure’, it may well not be your fault at all.

You should get advice from a specialist solicitor – preferably a local, specialist solicitor – as soon as possible.

Feel free to contact us if you have any questions arising from this article or regarding our personal injury claim services generally. Have a read of the article HERE, if you want to understand more about what will actually happen if you get in touch with us about making a personal injury compensation claim.

All initial enquiries are free of charge and without obligation to take things any further with us. In most cases, our personal injury claims services end up being completely free of charge to our clients.

We are accredited specialist solicitors in Elgin. You can contact us by phone on 01343 544077 or send us a Free Online Enquiry.